If you grew up in the southwest United States, if you can claim Hispanic heritage, or if you’ve lived in a community with a distinct Hispanic population, you are likely quite familiar with the numerous legends of “La Llorona” (The weeping woman). If, however, you grew up in central Pennsylvania (like I did) or in more rural areas of the midwest or northeast United States (like the majority of my students here in Iowa), chances are you have never heard the eerie tales of this weeping woman – this repentant, murderous mother.

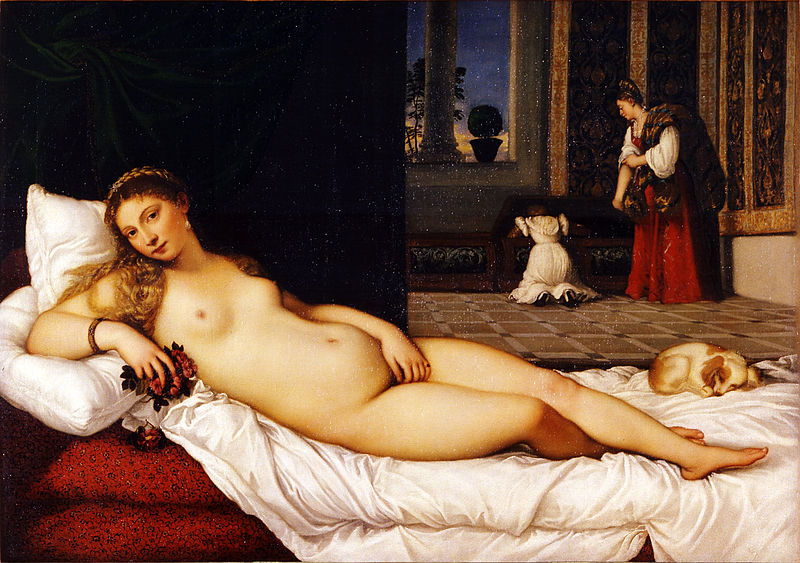

![La Llorona by ravage-eject]()

La Llorona – complete with the dark river at night and the bloody handprint of a child on her blouse

In my transatlantic women’s literature seminar this semester, I wanted to include a sample of US Latino texts as a way of encouraging students to view Spanish as a “second” language within the US rather than a entirely “foreign” one. Given that the course centered on paradigms of womanhood (female archetypes) like “la perfecta casada” (“the perfect wife”) and “La Malinche,” I dedicated the first class to “La Llorona.” There were three parts to my students’ first homework assignment:

- Students read two very abridged versions of the the Llorona legend: one that takes place in colonial Mexico and another in the 20th century US,

- They also read a short article on the Malinche/Llorona dichotomy that traces the evolution, and ensuing confusion and conflation of these two female figures in more recent cultural history (we had already read Octavio Paz’s “Hijos de Malinche”/”Sons-Children of Malinche” at the beginning of the semester), and

- Students were required to find an image of La Llorona and email it to me prior to class.

(The texts and assignments are available at the end of this post under “Resources”).

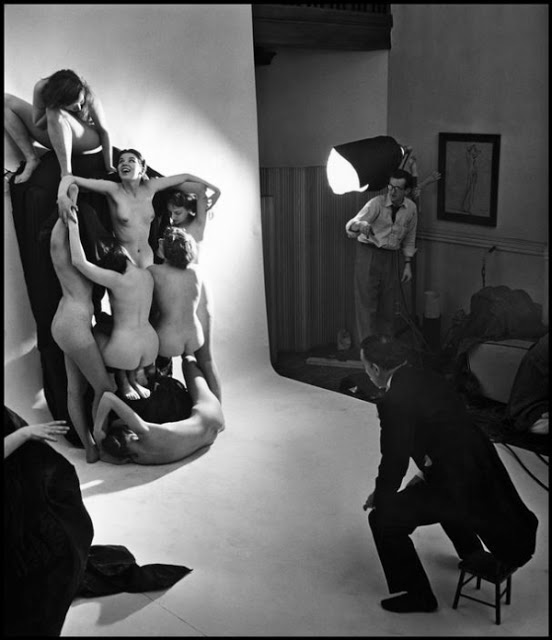

As I’ve mentioned before, I am a big fan of incorporating art and images into literature courses, and I wanted to start the class discussion by examining the diverse representations of La Llorona that exist today. This seemed like a great idea… until that morning when I received 18 versions of a dead or ghostly woman in my inbox! Just take a look at the Google Images page for “La Llorona”. Below is the most popular image that students sent me (at least 5 of the 18 selected it), followed by my “favorite” – aka – the most disturbing:

![http://citedatthecrossroads.net/chst332/files/2014/02/la_llorona_by_nativecartoon-d5qd7gc.jpg]()

“La Llorona” – Several of my students selected this image after reading two different versions of the Llorona legend.

![]()

The creepiest image of La Llorona that I received in my inbox – it appears that is a REAL baby, not just a doll….

After discussing the two different variations of the legend and images of La Llorona, we considered the power of such mythic tales. Why do they survive? What purpose do they serve? Who is the target audience? What lessons, or moralejas, do they communicate? For example, the most modern versions appear to be targeted at children, aiming to frighten them into obedience with some variation of…

“Don’t [cry / play by the river or arroyo / stay out past dark; etc. ]…

…or La Llorona will come and steal/kill you”.

To (over)simplify these narratives, in the colonial Mexican version, the woman bears the children of a white Spaniard – a man outside, and above, her own social class. When he refuses to marry her because of her Indian blood, she brutally stabs her children in a sudden moment of rage. She promptly laments her actions and roams the streets sobbing for her children, “Ayyyyy mis pobres hijos!” (Ayyyy, my poor children). She is arrested and condemned to death, but her ghostly spirit is said to continue roaming the streets at night in search of her children. In the modern US version, after marrying and having children, the woman becomes overwhelmed by her responsibilities at home and unhappy due to the lack of attention from her husband (who spends the majority of his time outside the home, at work, at bars, and with younger women). One day he leaves his wife, never to return. She blames the children for the failure of the marriage and her husband’s abandonment, drowning them in the Rio Grande. Upon realizing that their death does not bring back her husband, she goes mad, wailing (Ayyyy!) and searching for her dead children, then drowns herself in the river as she attempts to “recover” them.

Modern local legends allude to sightings of a terrifying, weeping female figure in a white dress who roams the riverbed stealing children who play nearby. Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries this versatile myth has, understandably, been exploited in Mexican horror films and popular culture.

![http://rebeccambender.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/787ee-peliculas-6541-imagen1.jpg?w=328&h=469]()

1960s Mexican horror film

![http://www.wesh.com/themeparks/halloween-horror-nights/la-llorona-haunted-house-announced-for-hhn/21449914#!PSLbB]()

Promo for a Halloween haunted house by Universal Studios

Today, “sightings” of La Llorona are occasionally reported on entertainment and “news” programs. In class we watched a brief YouTube video (in Spanish) that detailed variations of the “Llorona” myth in other Latin American countries before delving into the main feature of the news spot: rare video footage and sound recordings of a Llorona-sighting outside of Oaxaca. Supposedly, the wail of La Llorona could be heard on this video (my class was quite skeptical!). Unfortunately, in the time since I taught the class several weeks ago, that particular video has been removed from YouTube, but below is a link to another similar one that is quite useful. It also gives a summary of the main elements of the legend, but rather than footage of a “Llorona-sighting,” it includes a documentary-style segment of a psychic examining a local property where a family had apparently felt the presence of a woman’s spirit – presumably La Llorona. It’s sort of like Ghost Hunters… in Mexico:

In any case… since my course was centered on female identities in the Hispanic World, I led the discussion away from the innocent child victims and the paranormal and towards the impact that such stories might have on women. What do they tell us about the “bad mother” vs. the “good mother”? What norms did “La Llorona” transgress that placed her in a situation that provokes her murderous rage? How did she react in each instance? For example, both tales start with a “beautiful mestizo woman” who falls in love; both portray her subsequent filicide as a consequence of an unanticipated deceit or rejection; and both effectively punish the mother for all eternity. While the murder of one’s children indeed deserves to be castigated, the fact that male (paternal) behavior is absent or excused in these tales is revealing. The basic tenets of machismo are therefore upheld, as the man either deceives his wife or lover with no consequences, abandons her and his children in order to pursue his own desires, and/or refuses parental responsibilities – again, with no consequences. Thus the burden of responsibility falls on the woman, not merely for the well-being of her child(ren), but for ensuring the satisfaction of the male figure. Moreover, while the legend may warn young children to behave, the image of a beautiful, ultimately deceived and condemned woman serves as a warning to young women, wives, and mothers – do not aspire to marry outside your social class; do not complain if your husband does not devote as much attention to you after you have children; make sure you place the importance of your husband’s and children’s needs and desires above your own, etc. My class came up with a variety of themes that surfaced regarding woman-as-victim and the tale of La Llorona as a form of female social control - once the main “distraction” of child-murder was removed, that is.

![montaya-01]()

A confluence of female identities – La Llorona y La virgen de Guadalupe… Chicano artist Delilah Montoya aims to “evoke an identity” through her photography that celebrates connections between Latin America and the United States, which originate at the Border.

To continue this brief unit on US Latino literature and culture, during the second class we read two short stories by Sandra Cisneros – “Never Marry a Mexican” and “Woman Hollering Creek,” both taken from her 1991 collection of short stories, Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories. In these cuentos Cisneros deliberately employs mythic and historic female archetypes as a means of both characterizing her protagonists (and other characters) and critiquing the influence that such paradigms of womanhood can have on female culture. For example, rather than following in the footsteps of the mythic “Llorona” and drowning her children in the nearby arroyo to enact vengeance on her abusive husband, Cleofilas in “Woman Hollering Creek” abandons him, saving both herself and her children by crossing the river back into Mexico. On the way, Cleofilas and Felice, the independent woman who helps her escape, laugh like powerful “Gritonas” (hollering women) rather than weeping like the “Llorona”. And in “Never Marry a Mexican“ we see how the traitorous woman, “La Malinche,” is used as a subtext for the behavior and characterization of the protagonist, Clemencia.

Finally, in the third class we watched the 2002 film Real Women Have Curves, directed by Patricia Cardoso and based on the play by Josefina Lopez. We concentrated on the way in which Ana, a Mexican-American teenager, is positioned in opposition to her Mexican mother (Carmen). Each woman has a distinct idea of what constitutes a respectable, or ideal, female identity. Carmen’s traditional, conservative notions of family and femininity clash with Ana’s more rebellious sentiments regarding women’s independence and sexuality. Since this post has gotten a bit longer than I anticipated, I won’t go into much detail regarding these class preparations and discussions, but instead will include the discussion questions, assignments, and resources at the end of this post for interested readers. Feel free to leave comments, tips, or suggestions based on your experiences reading, viewing, or teaching these texts.

I’ll wrap up with a few images of the Virgin of Guadalupe that we examined during this final class. These modern, predominantly feminist renditions of La virgen de Guadalupe are a perfect way to illustrate the reinvention of female identities by way of a confluence and manipulation of the traditional and the modern. I began with the “original” representation of Our Lady of Guadalupe – the image that appeared on Juan Diego’s cloak in 1531, and which is on display today in Mexico City’s Basilica:

![]()

“Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe” (Our Lady of Guadalupe) – Mexico. This is the image that appeared on Juan Diego’s cloak in 1531; it is preserved and on display today at the Basilica in Mexico City.

I then showed them Alma Lopez’s “Our Lady” (1999), as the shape, form, and surrounding imagery share many similarities with the iconic image of La virgen de Guadalupe, yet Lopez’s (not-so)subtle refashioning is also one of the most scandalous and controversial representations to date.

![]()

“Our Lady” by Alma Lopez (1999)

Unlike the most popular images of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Lopez’s does not hide this female icon’s body or sexuality; she actively looks out and up, rather than passively averting the spectator’s gaze; she is poised more assertively, with her hands on her hips; she wears her cloak proudly, and its fabric is imbued with allusions to her indigenous past. With this image of the Virgin in a rose “bikini,” Lopez effectively calls out the paradox of the “Virgin-Mother” – the asexual woman who is most revered for her maternal role – as an impossible standard for “ordinary” Mexican women. By bringing female sexuality and corporeality into her depiction of a woman occupying the place of the “virgin-mother,” Lopez rejects the notion that women (particularly mothers) must repress or hide their sexuality. Along with this image, I also showed several of Yolanda Lopez’s portrayals from the 70s – specifically, this one, “Virgin Running” (1978). Lopez aimed to celebrate La virgen de Guadalupe – “the most ubiquitous female Latina” – by presenting her in ways that would connect her to real, modern women’s lives. This image is actually a self-portrait – Lopez depicts herself not as a demure, serene figure, but as a dynamic, active version of the Virgin of Guadalupe. I especially love her running shoes…

![]()

“Virgin Running” (self-portrait) by Yolanda Lopez (1978)

I was hoping that a few of my students would decide to incorporate US Latino texts into their final projects, and several actually did. One project examined the modern US and colonial Mexican versions of the legend of “La Llorona” in light of the influence of Protestantism and Catholicism respectively. Another incorporated “Never Marry a Mexican” into her discussion of how literary texts engage with and challenge the problematic dichotomies that define “appropriate” female identities (ex: good vs. bad; virgin vs. whore, etc.). And yet a third chose to discuss the mother-daughter relationships in three films that we studied during the semester: The Red Virgin (dir. Sheila Pye, 2012), Volver (dir. Pedro Almodovar, 2006), and Real Women Have Curves.

Overall, my class enjoyed reading these texts, and the majority of my students had little or no prior knowledge of the rich cultural heritage of Latinos in the US. It struck me that, even if some of them decide to become Spanish majors, they most likely will not have the opportunity take future Spanish courses that include these themes. Thus, after teaching this course and listening to my students’ positive feedback and responses on this unit, I think it’s crucial that professors of Spanish and Hispanic literature begin incorporating Latino texts into more general literature and culture courses when possible, rather than reserving them for entirely separate courses on Latino Studies or Latino or Chicano Literature. If we can place such an emphasis on Transatlantic courses (Spain and Latin America), especially given the vast cultural differences among Latin American countries, then certainly we can include US Latino literature as well. While specialized courses on Latino Studies, Literature, or Culture are of course necessary and should by no means be eliminated, they should not be the only outlet for discussion and dissemination of these very relevant works.

Phew… I’m exhausted. :-) For my readers who teach or have taught Latino Studies, what are some of your favorite texts to teach and discuss with students? What additional resources might work well in a Transatlantic Spanish literature course?

Resources:

Articles

- Leal, Luis. “The Malinche-Llorona Dichotomy: The Evolution of a Myth” in Feminism, Nation, and Myth. La Malinche. Eds. Rolando Romero and Amanda Nolacea Harris. Houston, TX: Arte Publico Press, 2005. 134-38.

- Paz, Laura. “‘Nobody’s Mother and Nobody’s Wife’: Reconstructing Archetypes and Sexuality in Sandra Cisneros’ ‘Never Marry a Mexican’”. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 6.4 (2008): 11-27. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/humanarchitecture/vol6/iss4/3

Texts: Short stories (cuentos) and Film

- La Llorona – Chapter 9: La Llorona, Mexico and Chapter 10: La Llorona, US, from Leyendas del mundo hispano, Eds. Susan M. Bacon, et al. NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000. (I believe my copy was a first edition, the chapters are likely different in the 2nd and 3rd eds.). Older editions of this text are available for only a few dollars. Contact me if you’re interested in my copies of these chapters.

- “Woman Hollering Creek” – click on this link to download a PDF of the short story. Alternatively, the web address is teacherweb.com/IN/Burris/Comber/Cisneros-Woman-HC.pdf

- “Never Marry a Mexican“- click on this link to download a PDF of the short story. Alternatively, the web address is http://www-classic.uni-graz.at/bibwww/summerschool/reader/CSAS/texts/Mod2_Heide_170709_SandraCisnerosNeverMarry.pdf

- Real Women Have Curves (dir. Patricia Cardoso, 2002) – The entire movies is available to watch online – just don’t download anything to watch it! It will play fine once you close the pop-ups.

Homework-discussion questions

(All are edit-able Microsoft Word documents):

![]()

![]()

Tres Prostitutas Decentes

Tres Prostitutas Decentes Ansias de volar

Ansias de volar La infinita sed.

La infinita sed.

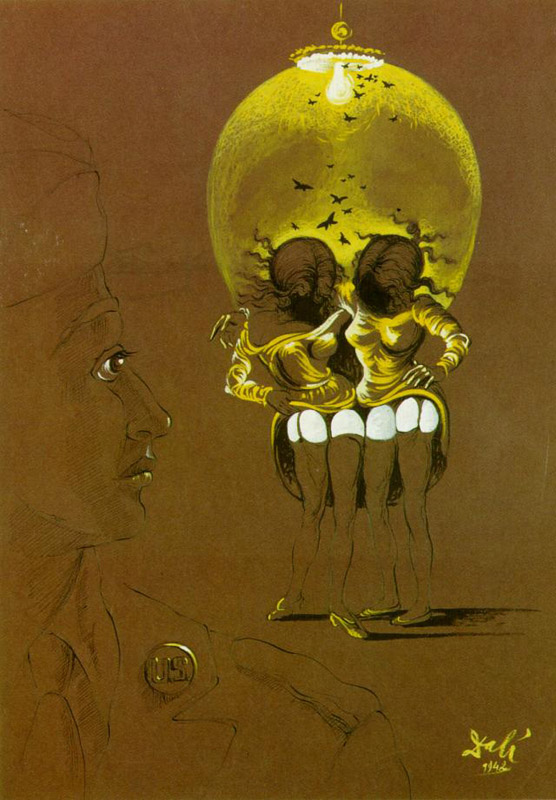

![La persistencia de la memoria [The Persistence of Memory] (1931) Salvador Dalí. The Persistence of Memory. 1931](http://www.moma.org/collection_images/resized/006/w500h420/CRI_257006.jpg)

![San Juan de la Cruz [St. John of the Cross] (1951)](http://media.liveauctiongroup.net/i/11432/11713349_1.jpg?v=8CE9E55E14CBC90)

![Leda atómica [Atomic Leda] (1949)](http://rebeccambender.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/d9d79-ledaatomica.jpg?w=416&h=576)

PRETTY WOMEN USE BIRTH CONTROL

PRETTY WOMEN USE BIRTH CONTROL

![A pittilesse Mother. That most unnaturally at one time murthe[red] two of her owne Children at Acton ... uppon holy thursday last 1616, the ninth of May. Beeing a gentlewoman named M. Vincent ... With her Examination, Confession and true discovery of all t[he] proceedings ... Whereunto is added Andersons Repentance w[ho] was executed ... the 18 of May 16[16].](http://rebeccambender.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/infanticide_1616.jpg?w=640&h=566)